Saturday, February 19, 2005

MALI01

A stone head found in a river on St. Vincent. On display at Ft. Charlotte.

MALI02

Small pottery head in the collection made for Saint Vincent and the Grenadines by Dr. I. A. Earle Kirby. Part of the collection is on display in Fort Charlotte.

MALI03

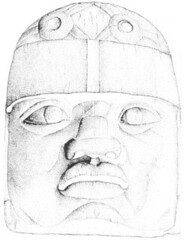

Olmec head from mainland Central America. Note that the appearance is much more African than Amerind.

Friday, February 18, 2005

Mysteries of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

There are, in my opinion, a number of mysteries associated with the island nation of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and the "Caribs" and "Black Caribs" who used to constitute its population.

The primary mystery is "Why are the Vincentians so 'nice'?". They are widely accepted as being the friendliest people in the Caribbean and that is such a pleasant condition for visitors that few even think about it. Vincentians, of course, accept it and take it for granted, but for those who are interested in history it is a noticeable anomaly. Like the other caribbean islands, the history of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is full of crises that were opportunities for violence, but the Vincentians managed to resolve peacefully. For example, the transition between post-colonial and contemporary governments in Grenada involved two military revolutions and an international war. The same transition in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines involved some strikes and an election.

This mystery is an important one, because what the world needs now is a friendly way to resolve its differences. If the nature of Vincentians is a natural, understandable phenomenon, it is possible for the rest of the world to learn it.

The second mystery was "What happened to the 'Yellow Caribs'? If you look at the british colonial sources, by the 1700s the majority of the native-born residents of the island were "Black Caribs" and there were only a handful of "Caribs" or "Yellow Caribs" left. On the other hand, the french sources portray a native population that are simply "Carib", with a small and unimportant group of "Black Caribs" that are only encountered when the "Caribs" gather for war. Were there lots of "Caribs" as the french see? Or just a handful in a sea of "Black Caribs" as the british see?

Associated with that mystery is the question of who the "Black Caribs" were anyway. The "Carib" part of their designation implies that there was some contribution from the Amerindian cultures that had migrated from (or through) the northeast corner of the eurasian landmass, with all that that implies; while the "Black" part of the designation implies a contribution from the african peoples who immigrated into the Caribbean, most, if not all, of them involuntarily under conditions of slavery. Did the term "Black Carib" merely indicate someone who acted like a "Carib" but with some modification to the appearance (such as a darker complexion or less straight hair) caused by inheritance of characteristic features of appearance more typical of african peoples?

Along with that mystery is the question of how the "Caribs" and "Black Caribs" are related to the "Ciboney" and "Taino" and other indigenous people of the caribbean area. Why did the "Taino" vanish while the "Caribs" remained as a viable colonial era culture? We can assume that the "Garifuna" or "Garinagu" are descendants of the people who were exiled to Rowaton Island from St. Vincent by the British in 1797, but what is their relationship to the people remaining on St. Vincent and Dominica who are identified as descended from "Caribs"; and how do they relate to the descendants of indigenous peoples in the other caribbean islands?

As we have shown in "Einstein's God and the Science of Zen" (http://eingod.karleklund.net ) the identification we call "racial" is a matter of genetically inherited appearance. The characteristics we lable as "ethnic", on the other hand, are determined by social behavior. We can no longer expect to have any objective measure of "race" among 17th and 18th century people, but we can identify three kinds of behavior patterns that were observable among caribbean peoples in that period: the "Conformist" behavior typical of pre-agricultural or hunter-gatherer peoples, the "Ideological" behavior typical of agricultural civilizations, including the european peoples who invaded the caribbean area; and "Transitional" behavior characteristic of people whose social groups had a higher population than the paleolithic hunter-gatherers but not so great that they had to adopt the fully post-neolithic societies that had popular religion and warrior castes in addition to farmers.

Transitional cultures are not well-understood, possibly because the evolution of the cultures between which the Transitional cultures fit were not understood before the publication of "Einstein's God". But one of the well-documented Transitional cultures were the Amerind cultures of the Pacific coast of what is now southwestern Canada and northwestern United States.

This is an area with substantial resources of fish, game and berries that could support a population much higher than the typical square kilometer per person of hunter-gatherer cultures. Their tribes had permanent chiefs and priests and redistributed resources among the groups controlling resources by the practice of "potlatch", in which groups gave away their surplus and received prestige. They did not, however, have the fully hierarchical structure of agricultural societies because the major social interaction between groups was through periodic potlatch feasts, not through the daily or weekly market interaction of agricultural villages.

The Caribs of St. Vincent, as described by Adrien Le Breton ("Historic Account of St. Vincent....") from personal experience, are "perfectly equal, and they recognize absolutely no official, chief or magistrate." This is characteristic of the hunter-gatherer stage of social evolution (see "Einstein's God") and normally is limited to groups of the order of a dozen in size who operate by a combination of conformity and individuality. This is generally found at a population density of about a square kilometer per person in open country. That would mean that St. Vincent would support a population of 350 or so persons in that kind of social structure.

However, Le Breton also says "...the fortunate complicity of the country astonishingly encourages the people's frenzy for total independence. ...the island ... is riddled with bays and hollows ...[and].. offers each father of a family the opportunity to choose ...his ideal site. far from any foreign constraint and completely safe ... to lead his life exactly as he pleases.

What happens in open country is that when the tribe gets too large to balance the conformity and individuality the tribe fissions. The equivalent in St. Vincent was that these tensions are relieved without fission: Le Breton describes them as "visit[ing] one another as frequently as possible".

In that way the Carib Transitional society could maintain the small unit structure necessary for a non-authoritarian society operated by consensus and conformity while maintaining a reasonably uniform culture over the whole island. This would allow them to practice a low intensity agriculture and exist at a significantly higher population density than hunter-gatherers in more open country.

Inevitably, the Amerinds who settled the Greater Antilles, where there was greater opportunity for intense, high-volume agriculture, developed ideological cultures like the mainland Amerinds These ideological cultures had no option but to collapse under the impact of an ideological culture with more powerful technology. The Taino, whose culture involved subservience to the supernatural and its worldly representatives, simply assumed that their gods were replaced by the gods of the Europeans.

The Caribs, on the other hand, could appropriate european technology without european ideology, because they did not have a central popular religion that provided a base for an authoritarian society. They not only quickly adopted iron tools and weapons, but, as described by Moreau de Jonnes (see Hulme, http://privatewww.essex.ac.uk/~phulme/Travel,%20Ethnography,%20Transculturation.htm ) when there were food shortages on St. Vincent they felt free to hire schooners in Trinidad to transport bulk cargo (bought with salvaged spanish coinage) unsuitable for the pirogues they used to get to Trinidad.

Thus the Caribs of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines had a Transitional Society that involved independence of small groups and individuals within an overall culture or ethnicity that made hospitality a deeply ingrained characteristic. They could, therefore, absorb the Africans who landed in small numbers and who were used to hunter-gatherer cultural norms; and in whom the need for independence had been reinforced by their experience of the middle passage if not plantation slavery. The Caribs could tolerate the french voyagers who came in small groups and adopted a certain amount of local customs. But they fought, to the extent their technology permitted, the British Colonists who brought ideology and authority and a foreign culture that called for settlement by force using large groups of armed men.

To the extent that the Carib Wars on Saint Vincent and the Grenadines prevented the full establishment of plantation slavery almost until the elimination of slavery, the Carib value system was not completely eradicated.

One might expect, therefore, that Vincentians might well be hospitable, not ethnocentric, and would prefer consensus to confrontation. What one might not expect, but is not unreasonable in this context, is that they prefer their ideology in small groups; leading to a large number of independent religious institutions, with a shifting membership. How this would affect the solidarity of political parties is something that professional politicians should think about, but I would not expect an intense ideological commitment. One can suspect that alliance to a political structure would be strongly dependent on the visibility of the political figures representing that political organization.

The mystery of the missing "Yellow Caribs" is probably an artifact of french and british xenophobia. The distinction between "Caribs" and "Black Caribs" was a political one. The British, being motivated to consider all the "Black Caribs" as either escaped slaves or their descendants, probably used a criterion similar to that used by Southern Anglo Americans in the post-Civil-War period--that "one drop of African blood" made someone "Black".

The french, on the other hand, being less racist, probably considered that anyone who acted like a "Carib" was a "Carib"; and only used the designation "Black Carib" for those indigenes who were so African in nature that they didn't like the French any better than the British. Since those motivations are irrelevant now, it makes little sense for us to distinguish between those people called "Carib" or "Black Carib" in the 18th century; and to refer to those people who are descended from the exiles on Rowaton Island in the manner that those people want to be referred to.

There remains one mystery that doesn't offer an easy explanation, the origin of the very first Black Caribs. The conventional explanation is that Africans came to places like St. Vincent by virtue of escape from slavery, either from the wreck of a slave ship or on a raft from Barbados. Dr. Earle Kirby, however, after a lengthy study of the question (and a remarkable collection of archaeological artifacts) has suggested that there was a visitation in the 1300s by an expedition from Mali. If so a population with both african and caribbean genetic characteristics could have existed long before europeans brought africans to the caribbean as slaves.

I'll post pictures of a stone figure found in a river on St. Vincent, a drawing of an Olmec stone monuments from the mainland, and a pottery head found on St. Vincent, all prehistoric. All have "racial"(i.e., appearance) characteristics more characteristic of Africa than America. They are posted as Mali 01, 02 and 03.

Thus, barring some unusual findings in DNA studies, one can assume that there was little intrinsic difference between the "Ciboney", "Carib" and "Taino" Amerinds--they merely represented stages in the same kind of social evolution that the Eurasian peoples went through, It was just the geography of Saint Vincent that gave the "Caribs" and "Black Caribs" of Saint Vincent the opportunity to evolve into such a uniquely admirable people.

This explanation, based, as it is, on a phenomenon characteristic of the mesolithic-neolithic transition is not likely to be easily accepted. But it is becoming clear that that transition is the source of a number of interesting phenomena. Potlatch, as we mentioned above, was an invention of the mesolithic-neolithic transition in the temperate rain forest of northwest North America. This kind of redistribution is also characteristic of the "big man" phenomenon on the South Pacific islands in a transitional culture that, like potlatch and Carib hospitality, was preserved to historic times by the particular geography in which it is found.

But other transitional phenomena may well be discovered through the close analysis of archaeological finds. It has been recognized that the local norm of melanin-concentration varies with latitude, being greater near the equator and less near the arctic. There was, however, one notable exception; those peoples who originated within 600 miles of the North and Baltic seas were noticeably melanin-deficient, enough so that they created the concept of "race" based primarily on melanin-concentration and secondarily on other features of appearance. While the explanation in "Einstein's God" makes it reasonable that appearance should be locally uniform and globally varied, it did not explain the melanin-deficiency of northern Europeans.

However, within the last year stable isotope analysis of remains dating from the Mesolithic to the late Neolithic has shown that as soon as it was introduced, northern Europeans abandoned fish and game for a grain-based diet. This provided the basis for a severe dietary deficiency of vitamin D, making those children with normal levels of melanin susceptible to rickets. This put a strong bias toward melanin-deficiency in the genetic inheritance of northern Europeans.

In a sense this acts similarly to the sickle-cell trait found in peoples living in areas subject to malaria. People with one sickle-cell gene are resistant to malaria, while those with the sickle-cell gene from both sides are subject to a characteristic anemia. Similarly, melanin-deficient people can obtain more of their vitamin D needs from the weak sunlight of northern latitudes but are susceptible to burning and melanoma in tropical latitudes. But just because melanin-deficiency is a kind of genetic disease doesn't mean that people who are called "white" should be considered genetically inferior.

This is not yet widely recognized, but when the implications are fully understood it may help to make the Vincentian lack of racism more understandable and more acceptable as a universal worldview.

The net result is that while Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a delightful place to visit even without history, it is even more fascinating with it.

The primary mystery is "Why are the Vincentians so 'nice'?". They are widely accepted as being the friendliest people in the Caribbean and that is such a pleasant condition for visitors that few even think about it. Vincentians, of course, accept it and take it for granted, but for those who are interested in history it is a noticeable anomaly. Like the other caribbean islands, the history of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is full of crises that were opportunities for violence, but the Vincentians managed to resolve peacefully. For example, the transition between post-colonial and contemporary governments in Grenada involved two military revolutions and an international war. The same transition in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines involved some strikes and an election.

This mystery is an important one, because what the world needs now is a friendly way to resolve its differences. If the nature of Vincentians is a natural, understandable phenomenon, it is possible for the rest of the world to learn it.

The second mystery was "What happened to the 'Yellow Caribs'? If you look at the british colonial sources, by the 1700s the majority of the native-born residents of the island were "Black Caribs" and there were only a handful of "Caribs" or "Yellow Caribs" left. On the other hand, the french sources portray a native population that are simply "Carib", with a small and unimportant group of "Black Caribs" that are only encountered when the "Caribs" gather for war. Were there lots of "Caribs" as the french see? Or just a handful in a sea of "Black Caribs" as the british see?

Associated with that mystery is the question of who the "Black Caribs" were anyway. The "Carib" part of their designation implies that there was some contribution from the Amerindian cultures that had migrated from (or through) the northeast corner of the eurasian landmass, with all that that implies; while the "Black" part of the designation implies a contribution from the african peoples who immigrated into the Caribbean, most, if not all, of them involuntarily under conditions of slavery. Did the term "Black Carib" merely indicate someone who acted like a "Carib" but with some modification to the appearance (such as a darker complexion or less straight hair) caused by inheritance of characteristic features of appearance more typical of african peoples?

Along with that mystery is the question of how the "Caribs" and "Black Caribs" are related to the "Ciboney" and "Taino" and other indigenous people of the caribbean area. Why did the "Taino" vanish while the "Caribs" remained as a viable colonial era culture? We can assume that the "Garifuna" or "Garinagu" are descendants of the people who were exiled to Rowaton Island from St. Vincent by the British in 1797, but what is their relationship to the people remaining on St. Vincent and Dominica who are identified as descended from "Caribs"; and how do they relate to the descendants of indigenous peoples in the other caribbean islands?

As we have shown in "Einstein's God and the Science of Zen" (http://eingod.karleklund.net ) the identification we call "racial" is a matter of genetically inherited appearance. The characteristics we lable as "ethnic", on the other hand, are determined by social behavior. We can no longer expect to have any objective measure of "race" among 17th and 18th century people, but we can identify three kinds of behavior patterns that were observable among caribbean peoples in that period: the "Conformist" behavior typical of pre-agricultural or hunter-gatherer peoples, the "Ideological" behavior typical of agricultural civilizations, including the european peoples who invaded the caribbean area; and "Transitional" behavior characteristic of people whose social groups had a higher population than the paleolithic hunter-gatherers but not so great that they had to adopt the fully post-neolithic societies that had popular religion and warrior castes in addition to farmers.

Transitional cultures are not well-understood, possibly because the evolution of the cultures between which the Transitional cultures fit were not understood before the publication of "Einstein's God". But one of the well-documented Transitional cultures were the Amerind cultures of the Pacific coast of what is now southwestern Canada and northwestern United States.

This is an area with substantial resources of fish, game and berries that could support a population much higher than the typical square kilometer per person of hunter-gatherer cultures. Their tribes had permanent chiefs and priests and redistributed resources among the groups controlling resources by the practice of "potlatch", in which groups gave away their surplus and received prestige. They did not, however, have the fully hierarchical structure of agricultural societies because the major social interaction between groups was through periodic potlatch feasts, not through the daily or weekly market interaction of agricultural villages.

The Caribs of St. Vincent, as described by Adrien Le Breton ("Historic Account of St. Vincent....") from personal experience, are "perfectly equal, and they recognize absolutely no official, chief or magistrate." This is characteristic of the hunter-gatherer stage of social evolution (see "Einstein's God") and normally is limited to groups of the order of a dozen in size who operate by a combination of conformity and individuality. This is generally found at a population density of about a square kilometer per person in open country. That would mean that St. Vincent would support a population of 350 or so persons in that kind of social structure.

However, Le Breton also says "...the fortunate complicity of the country astonishingly encourages the people's frenzy for total independence. ...the island ... is riddled with bays and hollows ...[and].. offers each father of a family the opportunity to choose ...his ideal site. far from any foreign constraint and completely safe ... to lead his life exactly as he pleases.

What happens in open country is that when the tribe gets too large to balance the conformity and individuality the tribe fissions. The equivalent in St. Vincent was that these tensions are relieved without fission: Le Breton describes them as "visit[ing] one another as frequently as possible".

In that way the Carib Transitional society could maintain the small unit structure necessary for a non-authoritarian society operated by consensus and conformity while maintaining a reasonably uniform culture over the whole island. This would allow them to practice a low intensity agriculture and exist at a significantly higher population density than hunter-gatherers in more open country.

Inevitably, the Amerinds who settled the Greater Antilles, where there was greater opportunity for intense, high-volume agriculture, developed ideological cultures like the mainland Amerinds These ideological cultures had no option but to collapse under the impact of an ideological culture with more powerful technology. The Taino, whose culture involved subservience to the supernatural and its worldly representatives, simply assumed that their gods were replaced by the gods of the Europeans.

The Caribs, on the other hand, could appropriate european technology without european ideology, because they did not have a central popular religion that provided a base for an authoritarian society. They not only quickly adopted iron tools and weapons, but, as described by Moreau de Jonnes (see Hulme, http://privatewww.essex.ac.uk/~phulme/Travel,%20Ethnography,%20Transculturation.htm ) when there were food shortages on St. Vincent they felt free to hire schooners in Trinidad to transport bulk cargo (bought with salvaged spanish coinage) unsuitable for the pirogues they used to get to Trinidad.

Thus the Caribs of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines had a Transitional Society that involved independence of small groups and individuals within an overall culture or ethnicity that made hospitality a deeply ingrained characteristic. They could, therefore, absorb the Africans who landed in small numbers and who were used to hunter-gatherer cultural norms; and in whom the need for independence had been reinforced by their experience of the middle passage if not plantation slavery. The Caribs could tolerate the french voyagers who came in small groups and adopted a certain amount of local customs. But they fought, to the extent their technology permitted, the British Colonists who brought ideology and authority and a foreign culture that called for settlement by force using large groups of armed men.

To the extent that the Carib Wars on Saint Vincent and the Grenadines prevented the full establishment of plantation slavery almost until the elimination of slavery, the Carib value system was not completely eradicated.

One might expect, therefore, that Vincentians might well be hospitable, not ethnocentric, and would prefer consensus to confrontation. What one might not expect, but is not unreasonable in this context, is that they prefer their ideology in small groups; leading to a large number of independent religious institutions, with a shifting membership. How this would affect the solidarity of political parties is something that professional politicians should think about, but I would not expect an intense ideological commitment. One can suspect that alliance to a political structure would be strongly dependent on the visibility of the political figures representing that political organization.

The mystery of the missing "Yellow Caribs" is probably an artifact of french and british xenophobia. The distinction between "Caribs" and "Black Caribs" was a political one. The British, being motivated to consider all the "Black Caribs" as either escaped slaves or their descendants, probably used a criterion similar to that used by Southern Anglo Americans in the post-Civil-War period--that "one drop of African blood" made someone "Black".

The french, on the other hand, being less racist, probably considered that anyone who acted like a "Carib" was a "Carib"; and only used the designation "Black Carib" for those indigenes who were so African in nature that they didn't like the French any better than the British. Since those motivations are irrelevant now, it makes little sense for us to distinguish between those people called "Carib" or "Black Carib" in the 18th century; and to refer to those people who are descended from the exiles on Rowaton Island in the manner that those people want to be referred to.

There remains one mystery that doesn't offer an easy explanation, the origin of the very first Black Caribs. The conventional explanation is that Africans came to places like St. Vincent by virtue of escape from slavery, either from the wreck of a slave ship or on a raft from Barbados. Dr. Earle Kirby, however, after a lengthy study of the question (and a remarkable collection of archaeological artifacts) has suggested that there was a visitation in the 1300s by an expedition from Mali. If so a population with both african and caribbean genetic characteristics could have existed long before europeans brought africans to the caribbean as slaves.

I'll post pictures of a stone figure found in a river on St. Vincent, a drawing of an Olmec stone monuments from the mainland, and a pottery head found on St. Vincent, all prehistoric. All have "racial"(i.e., appearance) characteristics more characteristic of Africa than America. They are posted as Mali 01, 02 and 03.

Thus, barring some unusual findings in DNA studies, one can assume that there was little intrinsic difference between the "Ciboney", "Carib" and "Taino" Amerinds--they merely represented stages in the same kind of social evolution that the Eurasian peoples went through, It was just the geography of Saint Vincent that gave the "Caribs" and "Black Caribs" of Saint Vincent the opportunity to evolve into such a uniquely admirable people.

This explanation, based, as it is, on a phenomenon characteristic of the mesolithic-neolithic transition is not likely to be easily accepted. But it is becoming clear that that transition is the source of a number of interesting phenomena. Potlatch, as we mentioned above, was an invention of the mesolithic-neolithic transition in the temperate rain forest of northwest North America. This kind of redistribution is also characteristic of the "big man" phenomenon on the South Pacific islands in a transitional culture that, like potlatch and Carib hospitality, was preserved to historic times by the particular geography in which it is found.

But other transitional phenomena may well be discovered through the close analysis of archaeological finds. It has been recognized that the local norm of melanin-concentration varies with latitude, being greater near the equator and less near the arctic. There was, however, one notable exception; those peoples who originated within 600 miles of the North and Baltic seas were noticeably melanin-deficient, enough so that they created the concept of "race" based primarily on melanin-concentration and secondarily on other features of appearance. While the explanation in "Einstein's God" makes it reasonable that appearance should be locally uniform and globally varied, it did not explain the melanin-deficiency of northern Europeans.

However, within the last year stable isotope analysis of remains dating from the Mesolithic to the late Neolithic has shown that as soon as it was introduced, northern Europeans abandoned fish and game for a grain-based diet. This provided the basis for a severe dietary deficiency of vitamin D, making those children with normal levels of melanin susceptible to rickets. This put a strong bias toward melanin-deficiency in the genetic inheritance of northern Europeans.

In a sense this acts similarly to the sickle-cell trait found in peoples living in areas subject to malaria. People with one sickle-cell gene are resistant to malaria, while those with the sickle-cell gene from both sides are subject to a characteristic anemia. Similarly, melanin-deficient people can obtain more of their vitamin D needs from the weak sunlight of northern latitudes but are susceptible to burning and melanoma in tropical latitudes. But just because melanin-deficiency is a kind of genetic disease doesn't mean that people who are called "white" should be considered genetically inferior.

This is not yet widely recognized, but when the implications are fully understood it may help to make the Vincentian lack of racism more understandable and more acceptable as a universal worldview.

The net result is that while Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a delightful place to visit even without history, it is even more fascinating with it.

Outline of Vincentian History

When we first came to Saint Vincent and the Grenadines there were two things that I noticed that surprised me. One was the relative lack of racism. This doesn't mean that there isn't a kind of snobism that ranks a lighter skin superior to a darker skin, but there isn't the blanket hostility by people of color toward the euroamerican minority that there is on some of the other islands.

I attributed that in part to the lack of an overpowering tourist industry with its requirement of servility and consequent resentment. But beyond that, the variety of color shades in the Vincentian complexion was comparable to French rather than former British islands. That meant that there had been friendlier relations in the past as well as the present.

The other thing that surprised me was the placement of guns in Fort Charlotte.

In most fortresses that overlook harbours, the guns point out to sea to aim at approaching ships. On St. Vincent the guns pointed inland to what was probably jungle or plantation when they were installed. Fort Charlotte was designed to defend against the islanders.

Finally, in January 2002, a talk by Prof. Hilary Beckles of UWI (Barbados) helped me to understand that these were two faces of the same phenomenon: the turbulent history of the island of St. Vincent and the Garifuna (or Black Carib) people. The following brief outline of St. Vincent and Garifuna history is based on Prof. Beckles' talk and several sources on the internet.

Early immigrants

After two migrations of pre-pottery people, there was a third migration of people who we call the Arawak, and who migrated from the areas now known as Guyana, Surinam and Venezuela around 160 CE and settled the Antilles. There were other movements around the Antilles and urbanization of the people on the bigger islands, but by 1300 or so St. Vincent was populated by a people who did subsistence farming and fished and spoke a language in the Arawak family and a trading pidgin we call Carib.

When the Spaniards arrived in the Americas in the early 1500s, they settled into the larger, urbanized islands like Cuba and Hispanola. In addition to mining and plantation agriculture they introduced foreign diseases and an oppressive system of forced labor that decimated local populations. African slaves were therefore imported into the New World beginning in 1517. By the 1600s slavery of Africans was fully established in the Caribbean.

Barbados is a flat island, well suited for the kinds of farming that can effectively utilize slave labor. But it is a relatively small island, so slaves who escaped from their plantations would be easily recovered unless they left the island on small boats. If they did they would tend to be blown to St. Vincent or the Grenadines. They and survivors of shipwrecks of slavers off the coast of Saint Vincent were taken in and assimilated into the Island Carib. Their descendants are called the Black Carib, known on the mainland as the Garifuna or Garinagu.

Europeans

The Carib resistance, mountainous terrain and lack of open flat areas kept European colonists away from St. Vincent long after other Caribbean islands had well-established European settlements. The island remained a nominal Spanish possession until 1627, when it was granted by the British crown to Lord Carlisle. The Caribs had tolerated small farms operated by a few French settlers but were resistant to the British plan of large slave-powered plantations.

In 1667 a meeting was held between Calinago (Carib) chiefs and Gov Willoughby of Barbados. This was a unique example of negotiation between Europeans and local authorities. The Europeans usually just took what they wanted by force, but this didn't work on St. Vincent. The indigenes were too fierce and the countryside too wild.

The British were already crowded in Barbados and they wanted land and indigenous "Yellow" (or "Red") Caribs as workers. They also wanted the Black Caribs to be returned to slavery, as the British considered them to be escaped slaves.

The Chiefs said the British were free to travel to and trade in St. Vincent but would get neither lands nor labour. They also assumed that, in return, their people would have free access to trade in Barbados. Willoughby returned two months later with 54 men to start a settlement and the Calinago chiefs considered the agreement broken and declared war which, with pauses, effectively lasted for 150 years.

In December of 1675 a committee of the Merchants of London had met with the Colonial Office to ask the government to provide the resources that would allow Governor Willoughby to "destroy all of the savages of the Windward Islands". This policy of deliberate genocide explains what finally happened.

In 1730 the British and French made an agreement that neither was to settle St. Vincent in view of the Carib hostility. In 1762 British started settlements anyway, which explains why the cannons were pointed inland.

The Caribs continued hostilities and, with the aid of the French recaptured the island in 1779, but it was returned to British sovreignity in 1783 by the same Treaty of Versailles which ended the American Revolution.

With the return of British troops and mercenaries from the American War, the scene was again set for open warfare. With the death of Principal Chief Chatoyer the British emerged as the victors in June of 1796. They then unleashed a massive man hunt, trapping and banishing 4,644 overly "rebellious" Black Carib to Baliceaux Island - where they were held on a 464 m. high cliff! Others manage to escape to South America and to the neighboring Antilles Islands.

Attempts at overwhelming the native Caribs having failed; the British deported most of them in 1797. Of those deported, the lighter-skinned "Yellow Caribs" were classified as "benign" and returned to St. Vincent. Today, many Creole-speakers on St. Vincent are descendants of the Yellow Carib. A number of Yellow Caribs were moved to a reservation at Sandy Bay, in the northeastern corner of St Vincent.

The remaining 2,026 captives were left on Honduras' Roatan Island with limited food and supplies on April 11, 1797. They were abandoned there because "not even an iguana could survive there", i.e. as a deliberate act of genocide. However Spaniards transported the Garifuna to the mainland. The Garifuna returned the favor, supplying food for the entire colony - which was dying of hunger because Spanish farming practices are not suited to the tropics.

The British abolished the trade in slaves in 1807 and abolished slavery in 1833. Thus the full application of the slave economy and the absence of free Black Caribs only had a life of 40 years on St. Vincent; while plantation slavery on, for instance, Cuba lasted from 1600 to 1880. Slavery therefore had less of a psychological impact in St. Vincent than it had on other Caribbean islands.

This was recognized in 2002 when the Unity Labor Party, having won the election of 2001, in parliament declared that the first National Hero of St. Vincent would be Chief Joseph Chatoyer, who led the guerilla war against the British Empire until his death in 1796.

It is the Yellow and Black Caribs of history, and the Garifuna of today, who provide a role model of strength and independence that allows the people of St. Vincent to have a self-image that requires no taint of inferiority no matter how dark (or light) their complexion.

It is that confidence in themselves that makes it possible for melanin-deficient people like Sally and me to be comfortable even as part of a tiny euroamerican minority.

I attributed that in part to the lack of an overpowering tourist industry with its requirement of servility and consequent resentment. But beyond that, the variety of color shades in the Vincentian complexion was comparable to French rather than former British islands. That meant that there had been friendlier relations in the past as well as the present.

The other thing that surprised me was the placement of guns in Fort Charlotte.

In most fortresses that overlook harbours, the guns point out to sea to aim at approaching ships. On St. Vincent the guns pointed inland to what was probably jungle or plantation when they were installed. Fort Charlotte was designed to defend against the islanders.

Finally, in January 2002, a talk by Prof. Hilary Beckles of UWI (Barbados) helped me to understand that these were two faces of the same phenomenon: the turbulent history of the island of St. Vincent and the Garifuna (or Black Carib) people. The following brief outline of St. Vincent and Garifuna history is based on Prof. Beckles' talk and several sources on the internet.

Early immigrants

After two migrations of pre-pottery people, there was a third migration of people who we call the Arawak, and who migrated from the areas now known as Guyana, Surinam and Venezuela around 160 CE and settled the Antilles. There were other movements around the Antilles and urbanization of the people on the bigger islands, but by 1300 or so St. Vincent was populated by a people who did subsistence farming and fished and spoke a language in the Arawak family and a trading pidgin we call Carib.

When the Spaniards arrived in the Americas in the early 1500s, they settled into the larger, urbanized islands like Cuba and Hispanola. In addition to mining and plantation agriculture they introduced foreign diseases and an oppressive system of forced labor that decimated local populations. African slaves were therefore imported into the New World beginning in 1517. By the 1600s slavery of Africans was fully established in the Caribbean.

Barbados is a flat island, well suited for the kinds of farming that can effectively utilize slave labor. But it is a relatively small island, so slaves who escaped from their plantations would be easily recovered unless they left the island on small boats. If they did they would tend to be blown to St. Vincent or the Grenadines. They and survivors of shipwrecks of slavers off the coast of Saint Vincent were taken in and assimilated into the Island Carib. Their descendants are called the Black Carib, known on the mainland as the Garifuna or Garinagu.

Europeans

The Carib resistance, mountainous terrain and lack of open flat areas kept European colonists away from St. Vincent long after other Caribbean islands had well-established European settlements. The island remained a nominal Spanish possession until 1627, when it was granted by the British crown to Lord Carlisle. The Caribs had tolerated small farms operated by a few French settlers but were resistant to the British plan of large slave-powered plantations.

In 1667 a meeting was held between Calinago (Carib) chiefs and Gov Willoughby of Barbados. This was a unique example of negotiation between Europeans and local authorities. The Europeans usually just took what they wanted by force, but this didn't work on St. Vincent. The indigenes were too fierce and the countryside too wild.

The British were already crowded in Barbados and they wanted land and indigenous "Yellow" (or "Red") Caribs as workers. They also wanted the Black Caribs to be returned to slavery, as the British considered them to be escaped slaves.

The Chiefs said the British were free to travel to and trade in St. Vincent but would get neither lands nor labour. They also assumed that, in return, their people would have free access to trade in Barbados. Willoughby returned two months later with 54 men to start a settlement and the Calinago chiefs considered the agreement broken and declared war which, with pauses, effectively lasted for 150 years.

In December of 1675 a committee of the Merchants of London had met with the Colonial Office to ask the government to provide the resources that would allow Governor Willoughby to "destroy all of the savages of the Windward Islands". This policy of deliberate genocide explains what finally happened.

In 1730 the British and French made an agreement that neither was to settle St. Vincent in view of the Carib hostility. In 1762 British started settlements anyway, which explains why the cannons were pointed inland.

The Caribs continued hostilities and, with the aid of the French recaptured the island in 1779, but it was returned to British sovreignity in 1783 by the same Treaty of Versailles which ended the American Revolution.

With the return of British troops and mercenaries from the American War, the scene was again set for open warfare. With the death of Principal Chief Chatoyer the British emerged as the victors in June of 1796. They then unleashed a massive man hunt, trapping and banishing 4,644 overly "rebellious" Black Carib to Baliceaux Island - where they were held on a 464 m. high cliff! Others manage to escape to South America and to the neighboring Antilles Islands.

Attempts at overwhelming the native Caribs having failed; the British deported most of them in 1797. Of those deported, the lighter-skinned "Yellow Caribs" were classified as "benign" and returned to St. Vincent. Today, many Creole-speakers on St. Vincent are descendants of the Yellow Carib. A number of Yellow Caribs were moved to a reservation at Sandy Bay, in the northeastern corner of St Vincent.

The remaining 2,026 captives were left on Honduras' Roatan Island with limited food and supplies on April 11, 1797. They were abandoned there because "not even an iguana could survive there", i.e. as a deliberate act of genocide. However Spaniards transported the Garifuna to the mainland. The Garifuna returned the favor, supplying food for the entire colony - which was dying of hunger because Spanish farming practices are not suited to the tropics.

The British abolished the trade in slaves in 1807 and abolished slavery in 1833. Thus the full application of the slave economy and the absence of free Black Caribs only had a life of 40 years on St. Vincent; while plantation slavery on, for instance, Cuba lasted from 1600 to 1880. Slavery therefore had less of a psychological impact in St. Vincent than it had on other Caribbean islands.

This was recognized in 2002 when the Unity Labor Party, having won the election of 2001, in parliament declared that the first National Hero of St. Vincent would be Chief Joseph Chatoyer, who led the guerilla war against the British Empire until his death in 1796.

It is the Yellow and Black Caribs of history, and the Garifuna of today, who provide a role model of strength and independence that allows the people of St. Vincent to have a self-image that requires no taint of inferiority no matter how dark (or light) their complexion.

It is that confidence in themselves that makes it possible for melanin-deficient people like Sally and me to be comfortable even as part of a tiny euroamerican minority.

Disney and the Caribs

According to Paul Lewis of the SVG Historical Society Disney executives insist that Caribs in Dominica be portrayed as cannibals. Adrian Fraser in his column (quoting Carib Chief Charles Williams) says that the scene will show Caribs roasting another Carib in the style of a barbecue. Furthurmore Disney people say the script cannot be changed.

That, of course, is nonsense. Scripts have been changed even with films in the can, if the change is necessary to market the film. And the easiest time to change a script is while it is just words on paper. What Disney doesn't understand is that a community that survived the attempted genocide by the British Empire is not likely to be fazed by a corporation that is dependent on popular approval.

Whether or not the Caribs roasted people, or even ate bits of them for ritual reasons, is, on the one hand, something for academics to argue about. Displaying it in a movie that is likely to be popular based on its predecessor is unnecessary promulgation of a racist myth for political purposes. A minor change in the script in which the europeans BELIEVE the Caribs are cannibals and in which the roastee is a european colonist, while the central characters discover, at the climax that the Yellow and Black Caribs are fierce freedom fighters defending their homes and independence would not only be much more acceptable to Caribbean academics, but would be considerably more acceptable to audiences in the Caribbean diaspora and the non-melanin-deficient international audience. And it would be a lot cheaper to change the script now, before any shooting, than to change the final cut after a lot of demonstrations.

There are lots of interesting questions about the Caribs that will be discussed in future blogs in this series. But it would be a useful thing if a lot of people showed that they care how the Garifuna and other peoples are portrayed in big production movies. It is too late in the twentyfirst century to slander an ethnic group simply out of ignorance and greed.

That, of course, is nonsense. Scripts have been changed even with films in the can, if the change is necessary to market the film. And the easiest time to change a script is while it is just words on paper. What Disney doesn't understand is that a community that survived the attempted genocide by the British Empire is not likely to be fazed by a corporation that is dependent on popular approval.

Whether or not the Caribs roasted people, or even ate bits of them for ritual reasons, is, on the one hand, something for academics to argue about. Displaying it in a movie that is likely to be popular based on its predecessor is unnecessary promulgation of a racist myth for political purposes. A minor change in the script in which the europeans BELIEVE the Caribs are cannibals and in which the roastee is a european colonist, while the central characters discover, at the climax that the Yellow and Black Caribs are fierce freedom fighters defending their homes and independence would not only be much more acceptable to Caribbean academics, but would be considerably more acceptable to audiences in the Caribbean diaspora and the non-melanin-deficient international audience. And it would be a lot cheaper to change the script now, before any shooting, than to change the final cut after a lot of demonstrations.

There are lots of interesting questions about the Caribs that will be discussed in future blogs in this series. But it would be a useful thing if a lot of people showed that they care how the Garifuna and other peoples are portrayed in big production movies. It is too late in the twentyfirst century to slander an ethnic group simply out of ignorance and greed.

Wednesday, February 16, 2005

Pictures

The pictures seem to be OK, but the website I took them from may not yet have discovered that I did something they didn't want me to. Keep an eye on the picture in the profile.

In the meantime, you can watch the site here as it develops.

In the meantime, you can watch the site here as it develops.

Picture Test

This is the "welcome" picture from the revised SVG page

Let's see if it works

Let's see if it works

Notes:02 /16 /05

Evidently the picture I used with my profile was taken from another of my websites. I'll have to find another picture and put it up somewhere more cooperative.

I'm revising the Saint Vincent and the Grenadines website that's presently reached through svg.karleklund.net Eventually it will be reachable through that address but for the moment it is at 2005.freehosting.net

You can read the all text pages and the penultimate Kingstown pages, but everything is potentially subject to revision.

I'm revising the Saint Vincent and the Grenadines website that's presently reached through svg.karleklund.net Eventually it will be reachable through that address but for the moment it is at 2005.freehosting.net

You can read the all text pages and the penultimate Kingstown pages, but everything is potentially subject to revision.

Monday, February 14, 2005

A reader sent some questions about Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. This is a version sanitized of personal references.

Question: I am a former Peace Corps Volunteer in the Caribbean and happened across your web site and blog. Thank you for all that work. I want to go back and read more thoroughly many of your entries

Answer: Feel free to ask any sort of question. If I don't have an answer I'll tell you.

Q: My husband and I are considering purchasing a place in St. Vincent. Part of the reason is that we have three “almost draft age” children and don’t like what is happening in the US.

A: I didn't like being drafted and I'm not pleased with the administration myself. But neither have we given up our citizenship. We looked at several islands as places to retire too before we settled on St. Vincent. We figure if it can’t work on St. Vincent it won’t work anywhere.

Q: We are Christians, but find ourselves in a great minority as we do not support Pres. Bush.

A: You may find some Christians to fellowship with. I think there are some 54 varieties of evangelicals besides the Anglican state church, the Catholics, the Methodists, the Adventists and the Salvation Army.

Q: We are not rich. My husband works for a college and I tutor at our local high school.

A: We are living on Tiaa-Cref and Social Security and what’s left from a dissolved partnership and Sally’s inheritance.

Q: But we have enough equity in our home that we are thinking of buying an apartment building (3 apartments), renting 2 to locals and keeping one for ourselves or friends and family.

A: We bought a big house with most of the inheritance and partnership, converted it to three apartments, live in one half the year, rent out another at scale to a member of the Taiwanese agricultural advisory team, and our caretaker lives in the other rent free. The tenants pay their own electric, phone, internet and bottled gas. Our rent is low—most people pay more.

Q: My husband and I were Peace Corps Volunteers in Barbados and are interested in St. Vincent because tourism has apparently NOT taken over. My question to you is how risky would it be to purchase this apartment building in the New Montrose area considering we would not be there more than about once a year for awhile?

A: Risky in what sense? If you have tenants you are less likely to have burglars. But we live in Villa which is probably less druggy but more expensive than Montrose, so the theft from us is more of fruit and garden truck than the valuables that we don’t have anyway.

Q: Do you think we could get reliable folks to manage it for us?

A: That IS a problem. We have been here for some time and have people who we trust. It took us a few years to find the people we have. We lost a lot of stuff and Sally lost a lot of orchids and we lost a dog before we figured out who we couldn’t trust, and one of the worst was the friend of a peace corps volunteer. Even the people you can trust sometimes change after a couple of years. I have no idea what we’d do if we lost any of the people we have. You can hire honest and competent professional managers but they are expensive.

Q: I have gotten the names of some local folks from a former PCV who he says are reliable and who might be willing to manage it for us. (The internet is amazing, isn’t it?)

A: You better meet them yourself.

Q: How would we be received when we are there visiting?

A: It depends. We are pretty quiet and not particularly dogmatic and thus a lot of people think we are Canadian. As it happens many of our close friends are ex-pats (Canadian or Chinese) but Vincies are generally very friendly and those we know quite well are quite close.

But I would suggest that you come down for a couple of weeks and sense it for yourself. There isn’t any of the hostility that you find in Antigua, St. Kitts or Grenada, very little of the criminality that you find in urban Jamaica or Trinidad, hardly any racism (I only heard “Honkey go home” once and then it was said in a New York accent).

People have told me that people from other islands come to St. Vincent for vacation. There are people of all shades of tan to black (but only a few percent of melanin-deficient european stock) and there is a certain snobbery based on lightness of color, but the relation is more like that on francophone islands rather than the sharp black/white line you often find on anglophone islands. There are some new stores run by (India) indians carrying chinese goods so we are getting sophisticated on the micro level, but we are still pretty caribbean at the core. But it is best to spend a couple of weeks seeing for yourself.

I would suggest emailing Shirley Jones at the Paradise Inn (paradinn@caribsurf.com), telling her I suggested it, and see what she can do for you. She is fixing up another hotel out in Argyle but the Paradise has apartments that allow you to make your own breakfast and get the day started early. She may be able to talk about people who can manage a place. And if you can come down between October and May you can see how we manage.

Q: We would like to “give back” to the island in some way if we do purchase property there and eventually would like to spend part of the year there.

A: Don’t worry—for the first few years you will be contributing to the economy a lot more than you intended or wanted to, e.g. the real estate tax is cheap, but there is a 20% purchase tax for off-islanders. After you settle in you’ll find things to do.

Q: As PCV’s it didn’t take us long to be received by locals in Barbados, under these circumstances would we also eventually be befriended by locals?

A: People say the Vincies are the friendliest people in the Caribbean, and I haven't seen any evidence to the contrary. Just remember that you are in THEIR country and the way they do things may be the way that suits the climate and the environment. When the British tried to do ethnic cleansing on the Garifuna and shipped them off to Rowatan Island they were brought to the mainland by the Spanish colonists who were starving to death. Their agricultural methods didn't work in the tropics. The Garifuna taught them how to grow food to survive.

The Garifuna, or Black Caribs, are a people of mixed african/amerindian heritage who survived the attempted genocide of the colonial nations. We still have much to learn from them.

.......................................

Anyone who has questions like that, or, for that matter, questions about any of my websites, should feel free to ask them. Worst that can happen is if I don't answer!

Question: I am a former Peace Corps Volunteer in the Caribbean and happened across your web site and blog. Thank you for all that work. I want to go back and read more thoroughly many of your entries

Answer: Feel free to ask any sort of question. If I don't have an answer I'll tell you.

Q: My husband and I are considering purchasing a place in St. Vincent. Part of the reason is that we have three “almost draft age” children and don’t like what is happening in the US.

A: I didn't like being drafted and I'm not pleased with the administration myself. But neither have we given up our citizenship. We looked at several islands as places to retire too before we settled on St. Vincent. We figure if it can’t work on St. Vincent it won’t work anywhere.

Q: We are Christians, but find ourselves in a great minority as we do not support Pres. Bush.

A: You may find some Christians to fellowship with. I think there are some 54 varieties of evangelicals besides the Anglican state church, the Catholics, the Methodists, the Adventists and the Salvation Army.

Q: We are not rich. My husband works for a college and I tutor at our local high school.

A: We are living on Tiaa-Cref and Social Security and what’s left from a dissolved partnership and Sally’s inheritance.

Q: But we have enough equity in our home that we are thinking of buying an apartment building (3 apartments), renting 2 to locals and keeping one for ourselves or friends and family.

A: We bought a big house with most of the inheritance and partnership, converted it to three apartments, live in one half the year, rent out another at scale to a member of the Taiwanese agricultural advisory team, and our caretaker lives in the other rent free. The tenants pay their own electric, phone, internet and bottled gas. Our rent is low—most people pay more.

Q: My husband and I were Peace Corps Volunteers in Barbados and are interested in St. Vincent because tourism has apparently NOT taken over. My question to you is how risky would it be to purchase this apartment building in the New Montrose area considering we would not be there more than about once a year for awhile?

A: Risky in what sense? If you have tenants you are less likely to have burglars. But we live in Villa which is probably less druggy but more expensive than Montrose, so the theft from us is more of fruit and garden truck than the valuables that we don’t have anyway.

Q: Do you think we could get reliable folks to manage it for us?

A: That IS a problem. We have been here for some time and have people who we trust. It took us a few years to find the people we have. We lost a lot of stuff and Sally lost a lot of orchids and we lost a dog before we figured out who we couldn’t trust, and one of the worst was the friend of a peace corps volunteer. Even the people you can trust sometimes change after a couple of years. I have no idea what we’d do if we lost any of the people we have. You can hire honest and competent professional managers but they are expensive.

Q: I have gotten the names of some local folks from a former PCV who he says are reliable and who might be willing to manage it for us. (The internet is amazing, isn’t it?)

A: You better meet them yourself.

Q: How would we be received when we are there visiting?

A: It depends. We are pretty quiet and not particularly dogmatic and thus a lot of people think we are Canadian. As it happens many of our close friends are ex-pats (Canadian or Chinese) but Vincies are generally very friendly and those we know quite well are quite close.

But I would suggest that you come down for a couple of weeks and sense it for yourself. There isn’t any of the hostility that you find in Antigua, St. Kitts or Grenada, very little of the criminality that you find in urban Jamaica or Trinidad, hardly any racism (I only heard “Honkey go home” once and then it was said in a New York accent).

People have told me that people from other islands come to St. Vincent for vacation. There are people of all shades of tan to black (but only a few percent of melanin-deficient european stock) and there is a certain snobbery based on lightness of color, but the relation is more like that on francophone islands rather than the sharp black/white line you often find on anglophone islands. There are some new stores run by (India) indians carrying chinese goods so we are getting sophisticated on the micro level, but we are still pretty caribbean at the core. But it is best to spend a couple of weeks seeing for yourself.

I would suggest emailing Shirley Jones at the Paradise Inn (paradinn@caribsurf.com), telling her I suggested it, and see what she can do for you. She is fixing up another hotel out in Argyle but the Paradise has apartments that allow you to make your own breakfast and get the day started early. She may be able to talk about people who can manage a place. And if you can come down between October and May you can see how we manage.

Q: We would like to “give back” to the island in some way if we do purchase property there and eventually would like to spend part of the year there.

A: Don’t worry—for the first few years you will be contributing to the economy a lot more than you intended or wanted to, e.g. the real estate tax is cheap, but there is a 20% purchase tax for off-islanders. After you settle in you’ll find things to do.

Q: As PCV’s it didn’t take us long to be received by locals in Barbados, under these circumstances would we also eventually be befriended by locals?

A: People say the Vincies are the friendliest people in the Caribbean, and I haven't seen any evidence to the contrary. Just remember that you are in THEIR country and the way they do things may be the way that suits the climate and the environment. When the British tried to do ethnic cleansing on the Garifuna and shipped them off to Rowatan Island they were brought to the mainland by the Spanish colonists who were starving to death. Their agricultural methods didn't work in the tropics. The Garifuna taught them how to grow food to survive.

The Garifuna, or Black Caribs, are a people of mixed african/amerindian heritage who survived the attempted genocide of the colonial nations. We still have much to learn from them.

.......................................

Anyone who has questions like that, or, for that matter, questions about any of my websites, should feel free to ask them. Worst that can happen is if I don't answer!